Dream Interpretation With Heterosexual Dating Couples

Misty R. Kolchakian1,2 and Clara E. Hill1

We examined the effectiveness of the Hill cognitive-experiential model of dream interpretation for working with male and female partners in heterosexual dating couples. Results showed that female partners who received dream interpretation (N = 20) had greater improvements in relationship well-being, insight, and gains from dream interpretation than female partners in the wait-list control group (N = 20). However, male partners who received dream interpretation (N = 20) did not make significant improvements as compared to male partners who did not receive dream interpretation (N = 20). Hence, couples dream interpretation may be more helpful for women than men. Greater effort may be needed to involve men in couples dream sessions in hopes that they will show more gains in relationship well-being and insight.

dream interpretation; couples; gender; relationship well-being; insight.KEY WORDS:

The vast literature on couples focuses more on marital rather than dating relationships. However, it seems important to focus on unmarried couples involved in committed relationships because they may be more responsive to change-oriented programs than married couples (Jacobson & Addis, 1993). It may be more difficult to treat relationship problems once they are established than to prevent the problems from occurring in the first place. Thus, treatment aimed at helping dating couples learn to express and understand themselves and their partners more effectively may help prevent future relationship struggles and reduce the divorce rate.

Dream interpretation may be one effective therapeutic intervention aimed at assisting dating couples in communicating difficult and important feelings and cognitions. Bynum (1993) suggested that working with dreams in therapy may help couples become closer and reach deeper levels of understanding, satisfaction, and communication within the relationship. Couples who learn the dream interpretation process can then use this skill outside of therapy to work on their dreams and their relationship (Delaney, 1993).

One model of dream interpretation that has been successfully used is the Hill (1996) model. The Hill model of dream interpretation has been tested empirically and has been shown to yield positive gains in satisfaction and insight for individual clients (Cogar & Hill, 1992; Diemer, Lobell, Vivino, & Hill, 1996; Heaton, Hill, Hess, Hoffman, & Leotta, 1998; Heaton, Hill, Petersen, Rochlen, & Zack, 1998; Hill, Diemer, Hess, Hillyer, & Seeman, 1993; Hill, Diemer, & Heaton, 1997; Hill et al., 2000, Hill et al., 2001; Wonnell & Hill, 2000) and for group clients (Falk & Hill, 1995). To our knowledge, however no method of dream interpretation has been empirically tested with couples. In the same way that individual dream interpretation has been found to lead to an individual's central conflicts even when the individual can not or is hesitant to articulate them, it may also facilitate couples in expressing concerns in their relationships that they may be hesitant to broach.

The Hill model, which was adapted for use with couples for the current

study, involves the same three stages of exploration, insight, and action. The

basic assumption of the Hill model is that exploration, insight, and action

are necessary components of effective dream interpretation as clients

reimmerse themselves into the dream in order to gain greater

self-understanding and insight. The modification of this approach for working

with dating couples is that in addition to the regular procedures of working

with the dream for the dreamer (see Hill, 1996), the dreamer's partner is

asked to project onto the dreamer's dream "as if it were his or her

own,"and both are asked to think about the dream for their relationship

(see Kolchakian & Hill, 2000 for more detail). This process helps to

ensure that the dreamer's partner does not interpret the dream for the

dreamer, but rather listens empathically and thinks about the dream for him or

herself and the relationship throughout the three stages of exploration,

insight, and action.

Hence, in the modified exploration stage, the therapist works with the

dreamer to describe and associate to each of the images in his or her dream.

Next, the dreamer's partner is asked to give associations (but not

descriptions) to each of the major images of the dream "as if it were his

or her own dream". For example, a male partner might bring in a dream

that he is being chased down the street by a police officer. First, he would

be asked to describe the image thoroughly and then associate to being chased

by a police officer. Then, the female partner would be asked to associate to

what it would be like to be chased if it were her dream. After both partners

associate to this first image, the male partner would be asked to describe and

associate to the next image, the image of the street. After he has given his

description and association to the street, the female partner would give her

association to the street "as if the street were in her dream."

During the modified insight stage, the therapist and dreamer first attempt to achieve some understanding of the dream and its meaning for the dreamer. The therapist then attempts to help the dreamer's partner understand what the dream might mean for his or her own life. An additional focus of the insight stage involves asking couples about how the dream and some of its images relate to the relationship. Using the previous example of being chased down the street by the police officer, the male partner might suggest that he often feels as though he is running from the demands of his partner on him in their relationship together. The female partner might say that she feels like she is being chased by the societal pressure to find the right partner and get married.

Once insight into the dreamer's feelings is obtained, the therapist works with the dreamer in the modified action stage to explore how he or she would like to change or whether change is even desirable. The change could involve changing the dream or actual changes in the dreamer's life. Next, the therapist asks the dreamer's partner what changes he or she would like to make in his or her own life given the insights gained from interpreting the dream as if it were his or her own dream. The therapist then works with both partners to determine how they could improve or maintain the relationship given what they discovered in the insight stage. At the end of the session, both members of the couple are asked to summarize what they have learned through the dream interpretation process about themselves as individuals, about their partner, and about their relationship.

The first purpose of the present study was to examine the outcome of dream interpretation. We hypothesized that couples who received dream interpretation would increase more in open communication, empathy, relationship satisfaction, and insight into dream (in terms of themselves, their partner, and the relationship) than would couples who did not receive dream interpretation.

Furthermore, we were interested in whether the effects of dream interpretation would differ by gender. No gender differences were found in a reanalysis of the data for individual dream interpretation (Hill et al., 2001), but we speculated that the presence of one’s partner might influence one’s ability to profit from dream interpretation. Durana (1996) found gender differences associated with changes in marital satisfaction, with women reporting more relationship changes in therapy than men. Given this finding, it seems plausible that women would report more relationship changes in dream interpretation than would men. Durana suggested that the gender differences may have been due to the fact that men are not socialized to report relational changes whereas women often have a greater understanding of relationship difficulties. Sacher and Fine (1996) also found gender differences in relationship satisfaction in dating couples and suggested that women may be more invested in their relationships than men. In addition, men and women may view intimate experiences differently. More specifically, Engel and Saracino (1986) found that in romantic relationships, women were more likely to favor verbal intimacy while men were more likely to favor sexual intimacy. Given that a previous study (i.e., Hill et al., 2001) did not find gender differences, but previous research suggests that gender differences are likely to exist, we chose to examine differences in results for men and women between treatment and control conditions as a research question.

A final purpose was to find out whether men and women gained more from dream interpretation that focused on their own dream as opposed to dream interpretation focused on their partner's dream. Previous research in individual dream interpretation (Hill et al., 1993) found that clients gained more from working with their own dreams rather than someone else's dream. But members of a couple might feel differently than unrelated individuals working on dreams because the other person is important in their lives.

METHOD

Design

In this study, we first compared the effects of couples dream interpretation to no treatment for male and female participants. Hence, 20 couples were randomly assigned to treatment and 20 couples were randomly assigned to a wait-list condition. Couples in the treatment condition completed pre-session measures, participated in two dream sessions separated by one week, and then completed post-session measures. Couples in the control condition completed pre-session measures, waited two weeks, and then completed the same measures again. Once they had completed the second round of measures, couples in the control condition participated in two dream sessions separated by a week, and then took the post-session measures. To examine the effects of treatment, male participants in the treatment condition were compared to male participants in the control condition, and female participants in the treatment condition were compared to female participants in the control condition for changes across time in relationship well-being and insight. To examine reactions to dream interpretation sessions, data for gains from dream interpretation were combined for males in the treatment and control conditions and females in the treatment and control conditions.

Participants

Clients

80 heterosexual individuals in dating relationships (40 men, 40 women; 35 White, 16 Asian American, 9 Hispanic American, 8 African American, 1 Native American, and 11 Other), ranging in age from 18 to 28 (M = 19.67, SD = 1.84) served as clients. Most participants (i.e., 73 of 80 individuals) were undergraduate students at a large mid-Atlantic U.S. university, and typically (i.e., 36 of 40 couples) at least one member of the couple was a student in an introductory psychology course and received research credit for participation. All participants had been dating exclusively for at least three months and were not married. Only one participant had been married previously. Individuals had known their partners from 3 to 108 months (M = 30.00 months, SD = 22. 11) and had been romantically involved from 3 to 54 months (M = 20.21, SD = 13.89), with 75 (94%) of the participants having considered the possibility of marrying their partners. The number of previous romantic relationships the participants had been involved in ranged from 0 to 5 (mode = 0). Participants were unaware of the hypotheses of this study and whether they were in the treatment or wait-list control condition.

Therapists

Seventeen therapists (12 women, 5 men; 12 European American, 2 Hispanic American, 2 African American, 1 Asian American), including the first author, participated in this study. All therapists were doctoral students in counseling or clinical psychology who had taken at least one practicum course and who had been trained in Hill's (1996) model for working with dreams for individuals and for couples. Their ages ranged from 22 to 38 years (M = 27.53, SD = 4.58), and the amount of therapy experience ranged from 10 to 108 months (M = 26.92, SD = 25.66). The total number of dream interpretation sessions therapists had previously conducted ranged from 2 to 28 (M = 8.54, SD = 7.61). The number of couples previously seen in any type of psychotherapy ranged from 0 to 5 (M = 1.46, SD = 1.51). Using 5 point scales (1=low, 5=high), therapists rated their belief in and adherence to the following theoretical orientations: 3.23 (SD = .97) on humanistic/experiential, 3.15 (SD = .80) on cognitive-behavioral, and 3.08 (SD = 1.12) on psychodynamic orientations.

Interviewers and Judges

Six undergraduates and the first author (all women; 6 European American, 1 African American; age M = 23.00, SD = 4.90) conducted follow-up telephone interviews with clients. Two of the undergraduates and the first author rated insight and coded the follow-up telephone interviews. Interviewers and judges were unaware of the experimental condition when doing interviews or making judgments.

Measures

Demographic Form

The demographic form for both clients and therapists asked for age, year in college, gender, and ethnicity. In addition, therapists were asked about their level of clinical experience, their level of experience with the Hill model of dream interpretation, and their theoretical orientation. The client demographic form also included information pertaining to the length of the romantic relationship, how long they had known their partner, whether they had considered/discussed marriage with one another, whether they had ever been married, and previous involvement in committed relationships

The Primary Communication Inventory (PCI; Locke, Sabaght, & Thomes in Navran, 1967) is a 25-item instrument designed to measure marital communication. The overall scale indicates the soundness of communication between two partners including their avoidance of unpleasant topics and their openness in expressing themselves to one another. Although the measure has been used mostly with married couples, the content of the items seemed applicable to dating couples. Respondents use a 5-point Likert scale (1=Never, 5=Very frequently) to answer items such as "How often do you and your partner talk with each other about personal problems?" An individual score is obtained by summing each item (after reverse scoring some items and transposing some items from the partner's questionnaire). Higher scores refer to more positively-viewed communication. Locke et al. reported that the PCI was correlated highly with the Locke-Wallace Marriage Relationship Inventory and was sensitive to changes due to therapeutic interventions. In the current study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) of the measure was .83.

The Self and Other Dyadic Perspective-Taking Scales (SDPT and ODPT; Long, 1987) Self perspective-taking has been defined as "the ability to understand what the other individual is thinking, to put oneself in another's place, and intellectually to understand without vicariously experiencing the other's emotions" (Hogan, 1969). Dyadic perspective-taking was defined by Long (1987) as an attempt to understand the point of view of the other person in the dyad. The SDPT scale consists of 13 items using a 5-point Likert scale (0= "does not describe me very well", 4= "does describe me very well"). Individuals respond to how well the statement describes their behavior with their partners (e.g. "Before criticizing my partner I try to imagine how I would feel in his/her place"). Scores are summed across items (some items are reverse scored) with higher scores representing greater perspective-taking tendencies. The ODPT scale measures the individual's perception of the perspective-taking of one's partner in the context of a relationship. The scale consists of 20 items using the same 5-point Likert-type scale. Individuals are asked to respond to how well the statement describes their partner's behavior (e.g. "My partner is able to accurately compare his/her point of view with mine"). Separate factor analyses indicated two similar factors for the SDPT and ODPT scales: Strategies (i.e. perspective-taking attempts made) and cognizance (i.e., global understanding and awareness of partner). The internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) for the SDPT scale was .86 for husbands and .88 for wives, and for the ODPT scale was .93 for husbands and .95 for wives. Wives' and husbands' perspective-taking scores were correlated positively with their own dyadic perspective-taking scores, indicating concurrent validity. In the current study, the internal consistency reliability estimate was .87 for the SDPT scale and .93 for the ODPT scale.

The Dyadic Satisfaction Scale (DSS; Spanier, 1976). is a 10-item subscale of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale and measures the quality of the romantic relationship as perceived by the members of the couple. Respondents use a 6-point Likert scale (0=All the time, 5=Never) for 8 of the items (e.g. "How often do you and your partner quarrel?"). The remaining two items use 6- and 7-point Likert scales to measure degree of happiness in the relationship and feelings about the future of the relationship. Spanier (1976) reported an internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) of .94. Numerous studies have found correlations in the expected direction with other measures of marital satisfaction (e.g., the Locke-Wallace Marital Adjustment Scale). In the current study, Cronbach's alpha was .79.

Gains from Dream Interpretation (Heaton et al., 1998) measures client perceptions of gains from the dream interpretation. Fourteen items using a 9-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 9=strongly agree) were developed based on responses to open-ended questions about what clients felt they gained from a dream interpretation session using the Hill (1996) model (e.g. "I learned a new way of thinking about myself and my problems"). A factor analysis revealed three scales: Exploration/Insight (7 items, alpha = .83), Action (5 items, alpha = .82), and Experiential (2 items, alpha = .79). The overall GDI correlated moderately with more general session outcome measures such as the Depth Scale from the Session Evaluation Questionnaire (Stiles & Snow, 1984) and Session Impact Scale-Understanding Scale (Elliot & Wexler, 1994). In the present study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) was .79 for the total scale.

Client Insight into Dream

After writing the dream, clients responded to the following questions about the dream: "What do you think this dream means to you? How would this interpretation help explain recent events in your life?" Trained judges assessed the level of insight into the client's written dream interpretation using a 9-point Likert scale (1=no insight, 9=high insight). Judges used the definition of insight from Hill et al. (1992), "the client expresses an understanding about himself or herself and can articulate patterns or reasons for behaviors, thought, or feelings. Insight typically involves an 'aha' experience whereby the client perceives himself or herself or the world in a new way. The client takes appropriate responsibility rather than blaming others, using 'shoulds' imposed from the outside world, or rationalizing" (pp. 548-549). A moderate correlation (r = .43) was reported between this measure of dream insight and therapist-rated client insight (Diemer et al., 1996) and between this measure and the Exploration/Insight subscale of the Gains from Dream Interpretation measure (r = .47; Hill, Nakayama, & Wonnell, 1998). Interrater reliabilities (Cronbach's alphas) of .93 (Falk & Hill, 1993), .91 (Diemer et al., 1996), .97 (Hill, Nakayama, & Wonnell, 1998), and .88 and .90 (Hill et al., in press) have been reported. In the current study, the interrater reliability (Cronbach's alpha) was .90.

Client Insight into Partner's Dream

In addition to writing an interpretation of one's own dream (as mentioned above), clients also wrote an interpretation of their partner's dream. Clients were asked to respond to the following questions about their partner's dream: "What do you think this dream means for your partner? How would this interpretation help explain recent events in your partner's life?" Trained judges assessed the client's level of insight into his or her partner's dream using the same 9-point Likert scale (1=no insight, 9=high insight) and the definition of insight. In the current study, the interrater reliability (Cronbach's alpha) was .89.

Client Insight Into the Relationship

Clients were also asked to respond to the following questions about their relationship: "What do you think this dream means for your relationship? How would this interpretation help explain recent events in your relationship?" Trained judges assessed the client's level of insight into the relationship using the same 9-point Likert scale (1 = no insight, 9 = high insight) and definition of insight. The interrater reliability (Cronbach's alpha) was .95.

Therapist Adherence

Therapists responded to the following three items using a 9-point scale (1=low, 9=high): "How completely did you do the exploration stage?" "How completely did you do the insight stage?" "How completely did you do the action stage?" and "How competent did you feel doing the dream interpretation with this couple?"

Procedures

Pilot Cases

Two couples each volunteered to participate in one session to test the adaptation of the Hill model to working with couples. Overall, the couples suggested that the sessions helped them understand their partners and their relationship better. One participant stated that "The dream session helped to put something hazy and almost unrecognizable into perspective so that now he and I can go over hurdles together. I learned a lot about myself too."

Therapist Training

Therapists first read literature on working with couples (e.g. Jacobson & Addis, 1993; Perlmutter & Babineau, 1983) and re-read the Hill (1996) book about dream interpretation. The therapist training was divided into three parts. First, a didactic presentation refamiliarized therapists with the basic concepts of the dream interpretation model and applied the principles to working with couples. Second, trainees practiced the mechanics of conducting a dream interpretation session with each other. Third, each therapist conducted a dream interpretation session with a volunteer couple and received feedback from a supervisor.

Participant Recruitment

Participants were recruited through flyers posted throughout campus, announcements in undergraduate and graduate classes, electronic mail announcements, sign up sheets for introductory to psychology course credit, and referral from participating couples. In the announcement, potential clients were offered the opportunity to have dream interpretation sessions with their partner if they were in a committed heterosexual relationship and were between the ages of 18 and 30 years. Interested couples were asked to call the principal investigator to learn more about the study or sign up on the introductory psychology sign up sheet. Approximately 50 couples expressed initial interest in participating, but 8 declined because of the time requirements for the study and/or because they had already fulfilled their credit requirements. The remaining two couples did not show up for their sessions.

Initial Contact

Potential clients were informed that they would complete measures and then have their first session as soon as possible (treatment condition) or would be scheduled for their first dream session in approximately two weeks when a therapist became available (wait list condition). Each participant was asked to bring a written copy of a recent dream to the first session.

Pre-Session Testing

After arriving for the session, each member of the couple signed a consent form and completed the demographic form, Primary Communication Inventory, Differentiation of Self Inventory, Other Dyadic Perspective-Taking Scale, Self Dyadic Perspective-Taking Scale, Spanier's Dyadic Satisfaction Subscale, interpretations of their own dream, their partner's dream, and how their dreams related to their relationship. The clients in the treatment condition began their session immediately after filling out the forms. Clients in the wait-list condition were reminded that they would return two weeks later (at which time they would complete the measures again before the first dream session).

Dream Interpretation Sessions

At the beginning of the session, the therapist reviewed the written dream the clients brought to the session to determine whether the length was appropriate. If the dream seemed too lengthy, the client was asked to select a portion of the dream to work with in the session. The first session focused on one partner's dream and the second session focused on the other partner's dream, with each couple choosing at the beginning of the first session whose dream would be focused on first. The second dream session was conducted one week after the first dream session was conducted. Each couple had two 90 to 120 minute dream interpretation sessions conducted by the same therapist, using the couples dream interpretation guidelines set forth in the therapist training.

Post-Session Testing

Immediately following each session, the therapist completed the Therapist Adherence measure, and each member of the couple completed the Gains from Dream Interpretation scale. Approximately one week after the second dream session, each member of the couple completed the Primary Communication Inventory, the Self Dyadic Perspective-Taking scale, the Other Dyadic Perspective-Taking scale, the Dyadic Satisfaction Subscale, and the interpretations of own dream, partner's dream, and the relationship.

Rater Training

Two raters were trained to rate insight for this study using data from previous studies until an interrater reliability (Cronbach's alpha) of .90 was attained. They then rated the actual written interpretations from the current study for the dreamer's dream, the partner's dream, and the relationship. All interpretations from each client were presented at the same time, but in random order, so that raters could compare across interpretations but were unaware of which interpretation they were rating (pre- vs. post-session). Also, the first author did not rate insight on the sessions she conducted.

RESULTS

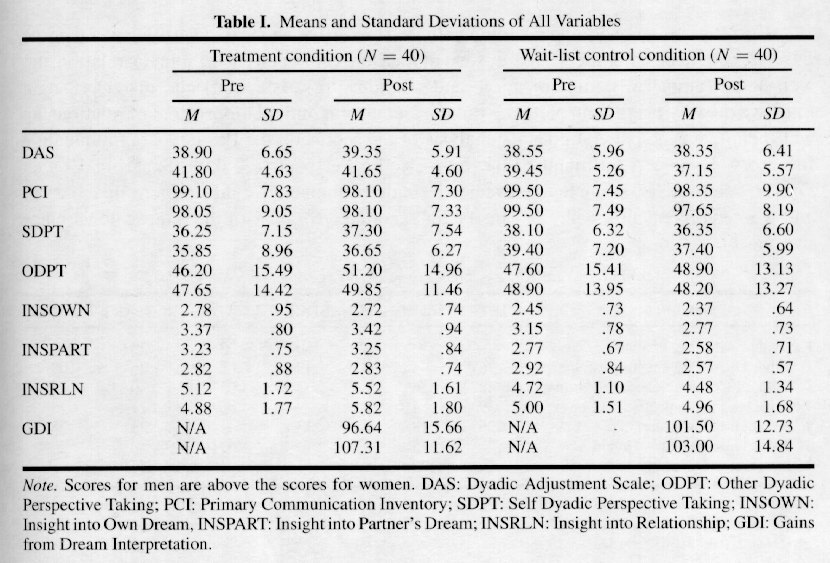

For the purpose of significance testing, an alpha level of .05 was used. The data for men and women were analyzed separately due to the dependence of the data (i.e., partners within couples would be expected to have related outcome scores). Table I shows the means and standard deviations for all variables used in the analyses for men and women.

Preliminary Analyses

Therapist Adherence

To determine whether therapists adhered to the Hill model, it was decided a priori that each therapist must rate himself or herself at least 5 or above on at least two of the three scales and at least 5 on the overall competence. All cases met this criterion, and thus no cases were dropped. In addition, the overall adherence scores were within one standard deviation of those reported in previous studies for individual dream interpretation (e.g. Heaton et al., 1998; Hill et al., 1997; Hill et al., in press).

All sessions met the requirements for therapist adherence in both sessions (i.e. scores of at least 5 for each item). Furthermore, none of the scores for session outcome variables were outliers. Hence, none of the cases were dropped.

Comparisons With Norms

Mean scores for all participants for the Primary Communication Inventory, Differentiation of Self Inventory, Dyadic Adjustment Scale, Self- and Other-Dyadic Perspective Taking Scales, change scores for judge-rated client insight, and Gains from Dream Interpretation were within one standard deviation of previously published scores for those measures (Navran, 1967; Spanier, 1976; Long, 1990; Hill et al., in press; Falk & Hill, 1995). Thus, it can be concluded that this sample was similar to previous samples on all measures.

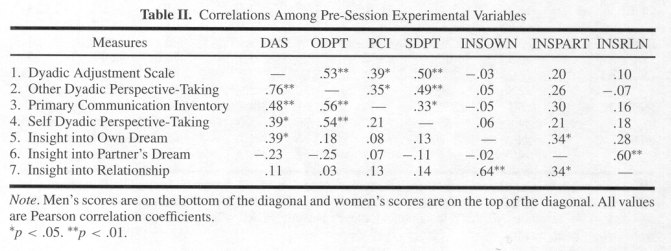

Correlations Among Pre-Session Measures

Correlations were computed among all pre-session measures to determine whether the measures could be combined. Two clusters of measures emerged (See Table II): relationship well-being (empathy, communication, and relationship satisfaction) and insight (insight into own dream, insight into partner's dream, and insight into relationship). For relationship well-being, a principal components analysis of the scores on the Primary Communication Inventory, Dyadic Adjustment Scale, Self Dyadic Perspective Taking Scale, and Other Dyadic Perspective Taking Scale revealed a single component for men (eigenvalue = 2.49) and women (eigenvalue = 2.42). This factor accounted for 62% of the total scale variance for both men and women. The internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) for the four scores was .75 for men and .73 for women. Thus, the four outcome measures were combined into one factor labeled "relationship well-being." A principal components analysis of insight into own dream, insight into partner's dream, and insight into the relationship revealed a single component for both men (eigenvalue = 1.71) and women (eigenvalue = 1.81). This factor accounted for 57% for men and 60% for women of the total scale variance. The internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) for the three scores was .60 for men and .61 for women. Thus, the three insight measures were combined into one factor.

Comparison of Conditions on Demographic Variables

Independent samples t-tests revealed no differences between the treatment and wait list conditions for client age, race, or any relationship variables (e.g. length of relationship, number of previous relationships, etc) for men or for women. Hence, random assignment resulted in two comparable groups on the measured client demographic variables.

Therapist Effects

To examine the therapist effects, all but one therapist were entered into simultaneous linear regression equations as dummy variables with change in relationship well-being, change in insight, and GDI as dependent variables. Because the regression was significant for change in relationship well-being, F(15, 64) = 2.13, p < .05, the data for this variable were centered (i.e. the therapists' mean for each variable was subtracted from the individual's scores for that variable). The centered data for relationship well-being were used for the remaining analyses. The regression analyses for change in insight and GDI were not significant, indicating no therapist effects; hence, raw data were used for these variables.

To further ensure that results were not biased by the first author's participation as a therapist in this study, regression analyses were examined to determine whether the first author's clients had different scores on the dependent variables of relationship well-being, insight, and GDI, as compared to clients of the other therapists. No significant differences were found, so all the first author's cases were included in the remaining analyses.

Finally, to examine whether therapist experience level was related to gains from dream interpretation, change scores on the relationship well-being outcome measure, and change in insight, correlations were computed. Therapist experience was not significantly correlated with any of the outcome measures, and thus was not considered in remaining analyses.

Therapist Adherence

The means and standard deviations on therapist adherence for the 80 sessions (Exploration, M = 8.01, SD = .92, Insight, M = 7.51, SD = .85, and Action, M = 6.83. SD = .97) were within one standard deviation of adherence scores reported for dream interpretation sessions by Wonnell and Hill (2000) for Exploration (M = 7.65, SD = 1.14), Insight (M = 7.30, SD = 1.08), and Action (M = 7.30, SD = 1.13), for sessions by Heaton et al. (1998) for Exploration (M = 7.41, SD = 1.50), Insight (M = 6.90, SD = 1.57), and Action (M = 6.17, SD = 1.42), and for sessions by Hill, Diemer, and Heaton (1997) for Exploration (M = 7.25, SD = .97), Insight, (M = 6.47, SD = 1.19), and Action (M = 6.08, SD = 1.33). Hence, therapists' adherence was similar to that of therapists in previous studies of individual dream interpretation.

Motivation Check

Because results may have varied based on whether or not the partner signed up for the study, we tested whether results differed on the basis of who signed up, separately for men and women. Independent sample t-tests comparing the 30 women who signed up for the study to the 10 women who did not sign up were not significant for any of the dependent variables. Similarly, independent sample t-tests comparing the 10 men who signed up for the study to the 30 men who did not sign up were not significant for any of the dependent variables. Hence, there were no differences based on whether or not the person signed up.

We also wondered whether introductory psychology students would have different outcomes from non-introductory psychology students, given that the former received course credit for participation but the latter did not. To test differences between these two groups, separate independent sample t-tests were conducted with course as the independent variable and change in relationship well-being, change in insight, and GDI as the separate dependent variables. None of these tests were significant for men or women.

Changes in Relationship Well-Being and Insight

1 x 2 ANOVAs were conducted separately for men and women, with condition as the independent variable and change in relationship well-being and change in insight as the dependent variables. For women, the main effect for condition (dream interpretation vs. wait list control) was significant for relationship well-being, F(1, 38) = 4.24, p < .05, and insight, F(1, 38) = 6.16, p < .05, such that women who received dream interpretation improved more in relationship well-being and gained more insight than women who did not receive dream interpretation. For men, neither main effect for condition was significant. Hence, women gained in relationship well-being and insight, whereas men did not.

Gains From Dream Interpretation

For this analysis, the treatment and control groups were combined. An ANOVA with gender as the independent variable and GDI as the dependent variable was significant, F(1,78) = 4.11, p < .05, with women scoring higher than men. Hence, women made more gains than did men from dream interpretation sessions.

Working on Own Dream vs. Partner's Dream

For this analysis, the treatment and control groups were combined. A paired samples t-test was conducted to compare scores on the GDI for working on one's own dream to scores on the GDI for working on the partner's dream. Results showed no differences between the two scores for men, t(39) = .02, p > .05, or for women, t(39) = -.72, p > .05. Hence, there were no differences in gains from dream interpretation when participants focused on their own dreams versus their partners' dreams.

DISCUSSION

This study found that women who received couples dream interpretation improved more in relationship well-being, insight, and gains from dream interpretation than women on a wait list. In contrast, men who received dream interpretation did not make significant improvements as compared to men on a wait list. These results are consistent with Durana (1996), Sacher and Fine (1996), and Engel and Saracino (1986), who found that women were more likely to report relationship changes over time as compared to men. Furthermore, the verbal sharing that was requested in the couples dream interpretation sessions may have appealed more to the women than the men, and thus the men may have been less interested in and comfortable with the sessions.

In addition, it appears that using the adapted Hill model for couples allowed women to learn more about themselves, their partners, and their relationships. The Hill method of dream interpretation has demonstrated gains in judge-rated insight (e.g. Hill et al., 2000; Wonnell & Hill, 2000; Hill et al., 2001; Rochlen et al., 1999; Zack & Hill, 1998; Heaton et al., 1998; Hill, Diemer, & Heaton, 1997; Diemer et al., 1996; Falk & Hill, 1995; Hill et al., 1993) for individuals and for groups (Falk & Hill, 1995), so it seems logical that the adapted model showed gains in insight for women. Interestingly, men seemed to respond differently in couples’ dream interpretation than they have in individual dream interpretation (i.e., a reanalysis of the Hill et al., 2001, data revealed no gender differences). The interpersonal nature of the couples dream interpretation may be threatening to men. More specifically, men and women may be more likely to adhere to the social norms/roles they learned growing up (e.g., women talk about feelings, men try to solve problems), especially in a new territory such as dream interpretation.

Working on Own Dream vs. Partner's Dream

No differences were found in self-reported gains in dream interpretation when interpreting one's own dream as compared to projecting onto the partner's dream. In other words, both men and women reported gains from interpreting their own dream as well as from interpreting their partner's dream "as if it were their own." In contrast, Hill, et al. (1993) found that interpreting one's own dream led to greater depth and insight than interpreting another person's dream. An important difference between the Hill et al. study and the current study is that in the Hill et al. study participants projected onto an unknown person's dream, whereas in the current study participants projected onto their partners' dreams. It would make sense that one might feel a stronger connection to a dream of someone with whom one feels close and connected, as opposed to the dream of some unknown person. Also, it may be that it is easier for members of a couple to project onto their partners' dream because they have shared some of the same waking life experiences that day or week. The lack of differences between the two types of sessions in terms of self-rated gains in dream interpretation suggests that both sessions were meaningful for participants and that the dreamer's partner gained from being present for their partner's dream session.

Limitations

One limitation of the current study is that we were not able to assess separate aspects of relationship well-being (i.e., communication, relationship satisfaction, empathy) because they were so highly correlated. A second limitation is the potential bias in examining insight via judge ratings, given that judges read only the dream and the dreamer's interpretation of that dream. Another limitation is that the dating couples in the current study may have been different from dating couples who seek counseling. Dating clients who are not distressed in their relationships may not be as motivated to change their relationships as clients who seek couples counseling. Hence, generalizations to a client population should be made with caution. In addition, clients participated in only two sessions of dream interpretation. Clients who were distressed when the study began may have required more than two sessions to notice any improvement. There may have also been a confound given that couples were allowed to choose which partner would share his or her dream in the first session. Finally, the use of graduate student therapists is another limitation. Most of the therapists had experience with dream interpretation, but only a few had experience working with couples.

Implications

The results suggest that dream interpretation can be used to help female clients gain insight and relationship well-being. Perhaps changes in one member of a couple would promote positive change in the partner, thus improving the relationship. Future research needs to test whether dream interpretation would be a helpful tool to use in the course of longer-term couples counseling.

Similar to more traditional forms of couples therapy, greater efforts may be needed to involve men in the process of dream sessions. According to Shay (1996), it is important to respect men's reluctance to share openly. Also, Shay suggested the importance of communicating with a resistant man in a language that he can understand as opposed to the "emotion-speak" or "insight-speak" associated with therapy and dream interpretation. These suggestions seem important mainly in couples dream interpretation, as opposed to individual dream interpretation, in light of findings by Hill et al., (2001) that men and women gained equally from dream interpretation in individual sessions.

Furthermore, it may be necessary to alter the adapted Hill model for working with couples so that men can show more gains in relationship well-being and insight. Shay suggested that it may be important for the therapist to model disclosure for the reluctant man and to narrow the gap between the therapist as expert and male client as needy. Also, Shay suggested validating client strengths and offering empathy in tolerable doses for male clients. Given these suggestions, it may be beneficial to train therapists to work with men in the course of couples dream interpretation and to prepare them for the resistance that may arise. This suggestion would need to be empirically tested, however. Finally, it may also be important to assess the goals of both members of the couple at the onset of dream exploration to assist both men and women in becoming invested in the process and to ensure that both partners get their needs met.

In terms of future research, it would be interesting to compare the behavior of male and female clients in individual dream sessions to the behavior of male and female partners involved in couples' dream sessions to see how they differ. Also, it would be important to study long-term outcome when working with dreams in couples therapy to see whether dream interpretation has any lasting effects. Finally, future research should compare dream interpretation to other structured methods for working with couples (e.g. communication training) to help determine whether the improvements in relationship well-being and insight into the relationship found in the current study were the result of dream interpretation or of some other aspect of the dream sessions (e.g. having both partners present and communicating). We believe that dream interpretation allows partners to access their feelings in the relationship more quickly than other structured methods, but this assertion needs to be empirically tested.

REFERENCES

Bynum, E.B. (1993). Families and the interpretation of dreams: Awakening the intimate web. New York: Harrington Park Press.

Cogar, M.C. & Hill, C.E. (1992). Examining the effects of brief individual dream interpretation. Dreaming, 2(4), 239-248.

Delaney, G. (1993). New directions in dream interpretation. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Diemer, R.A., Lobell, L.K., Vivino, B.L., & Hill, C.E. (1996). Comparison of dream interpretation, event interpretation, and unstructured sessions in brief therapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43(1), 99-112.

Durana, C. (1996). Bonding and emotional reeducation of couples in the Pairs training: Part II. American Journal of Family Therapy, 24(4), 315-328.

Elliot, R., & Wexler, M.M. (1994). Measuring the impact of sessions in process-experiential therapy of depression: The Session Impacts Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 41, 166-174.

Engel, J.W., & Saracino, M. (1986). Love preferences and ideals: A comparison of homosexual, bisexual, and heterosexual groups. Contemporary Family Therapy, 8, 775-780.

Falk, D.R. & Hill, C.E. (1995). The effectiveness of dream interpretation groups for women undergoing a divorce transition. Dreaming, 5(1), 29-42.

Hall, C. & Van de Castle, R. (1966). The content analysis of dreams. New York: Appleton-Century-Croft.

Heaton, K.J., Hill, C.E., Hess, S.A., Leotta, C., & Hoffman, M. (in press). Assimilation of a dissociative client's central problematic theme in brief psychotherapy involving recurrent and non-recurrent dreams. Psychotherapy.

Heaton, K.J., Hill, C.E., Petersen, D.A., Rochlen, A.B., & Zack, J.S. (1998). A comparison of therapist-facilitated and self-guided dream interpretation sessions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45(1), 115-122.

Hill, C.E. (1996). Dreams and therapy. Psychotherapy Research, 6(1), 1-15.

Hill, C.E. (1996). Working with dreams in psychotherapy. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hill, C.E., Diemer, R., Hess, S., Hillyer, A., & Seeman, R. (1993). Are the effects of dream interpretation on session quality, insight, and emotions due to the dream itself, to projection, or to the interpretation process? Dreaming, 3(4), 269-280.

Hill, C.E., Diemer, R.A., & Heaton, K.J. (1997). Dream interpretation sessions: Who volunteers, who benefits, and what volunteer clients view as most and least helpful. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 44(1), 53-62.

Hill, C.E., Kelley, F.A., Davis, T.L., Crook, R.A., Maldonado, L.E., Turkson, M., Wonnell, T.L., Veerasamy, S., Zack, J.S.,. Rochlen, A.B., Kolchakian, M.R., Codrington, J. (2001). Effects of client characteristics, type of dream, and waking life vs. parts of self interpretation on session outcome and insight into dreams in dream interpretation. Dreaming.

Hill, C.E., Nakayama, E.Y., & Wonnell, T.L. (1998). The effects of description, association, or combined description/association in exploring dream images. Dreaming, 8(1), 1-13.

Hill, C.E., Zack, J., Wonnell, T., Hoffman, M.A., Rochlen, A., Goldberg, J., Nakayama, E., Heaton, K.J., Kelley, F., Eiche, K., Tomlinson, M., & Hess, S. (2000). Structured brief therapy with a focus on dreams or loss for clients with troubling dreams and recent losses. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 90-101.

Jacobson, N.S. & Addis, M.E. (1993). Research on couples and couple therapy: What do we know? Where are we going? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(1), 85-93.

Kolchakian, M.R., & Hill, C.E. (2000). A cognitive-experiential model of dream interpretation for couples. In L. Vandecreek & T.L. Jackson (Eds.), Innovations in clinical practice: A source book, 18, 85-101.

Long, E.C.J. (1987). Perspective-taking as a determinant of marital adjustment and propensity to divorce (Doctoral dissertation, Oregon State University). Dissertation Abstracts International, 48, 8A.

Navran, L. (1967). Communication and adjustment in marriage. Family Process, 6, 173-184.

Perlmutter, R.A. & Babineau, R. (1983). The use of dreams in couples therapy. Psychiatry, 46, 66-72.

Rochlen, A., Ligiero, D., Hill, C. E., & Heaton, K. Preparation for dreamwork: Training for dream recall and dream interpretation. (1999). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46, 27-34.

Sacher, J.A., & Fine, M.A. (1997). Predicting relationship status and satisfaction after six months among dating couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58(1), 21-32.

Shay J.J. (1996). "Okay, I'm here, but I'm not talking!" Psychotherapy with the reluctant male. Psychotherapy, 33, 503-513.

Spanier, G.B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38, 15-28.

Stiles, W.B., & Snow, J.S. (1984). Dimensions of psychotherapy session impact across sessions and across clients. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 23, 59-63.

Stuart, R.B. (1980). Helping couples change: A social learning approach to marital therapy. New York: The Guilford Press.

Van de Castle, R.L. (1994). The dreaming mind. New York: Ballantine Books.

Wonnell, T., & Hill, C. E. (in press). The effects of including the action stage in dream interpretation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47.

Zack, J., & Hill, C. E. (1998). Predicting dream interpretation outcome by attitudes, stress, and emotion. Dreaming, 8, 169-185.

1

Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland.2

Correspondence should be directed to Misty R. Kolchakian, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742.